I attended worship recently at an out-of-town congregation during a consultation trip. As it happened it was a communion Sunday. I’m always interested in observing how congregations perform the two Ordinances–Communion (Lord’s Supper) and baptism. Especially in congregations of the Free Church tradition there is the promise of cultural and contextual novelty in the practices surrounding those ordinances—which is not to say that is always a good thing. They tend to provide a contrast to the liturgical churches who tend to be guided more by Tradition than by interpretation or predilection.

Unfortunately, despite my best efforts to participate in the ritual that Sunday I found myself becoming more irked at what has become one of my ecclesiastical pet peeves: the tendency of pastors to offer additional homilies, devotional thoughts, “interpretations,” or just plain ramblings just before the presentation of the elements. What is it with today’s pastors that they feel they need to “interpret” the Lord’s Supper in “creative” ways? Why interpret it at all? It’s a communal rite and ritual whose meaning arises from its practice in the community—not in how well or how creative a preacher is in spinning “another way to look at it.” As a symbol the Lord’s Supper carries the weight of its meaning through Tradition and via its practice, which needs no “interpretation.”

What tends to happen, inevitably, is that the “explanation” or “interpretation” of the practice usually results in the pastor talking about anything BUT what the symbol or ordinance is about. One month the Lord’s Supper is about “forgiveness,” but the next time it’s about “love” or about “justice,” or about “hospitality” or whatever it is that the pastor feels the need to emphasize. Sometimes an attempt is made to tie the explanation into the topic of the sermon (anything from “being a family” to stewardship). But unless the sermon was about communion, then we’re back to interpreting the Lord’s Supper as something other than what it is.

In my worst moments I’m straining to send a telepathic message straight to the frontal lobe of the pastor yelling, “I know what this is about, please don’t explain it, it speaks for itself! If you HAVE to say something, then just say the words of institution!” In this I am in accord with my Episcopalian friends who are fond of saying, “There’s no need to “invent” new ways of praying or for the liturgy. The Church has already said it and we have the words.” Ironically, then, the best way to inculcate the meaning of the Lord’s Supper is to repeat the words of institution every time the ritual is observed rather than try to “explain” it a different way every time.

Some have responded to my plea for “just the facts” (just extend the invitation and recite the words of institution) when it comes to presenting the Lord’s Supper by saying that there’s a need to “explain” it because so many people today don’t know the ritual and what it means. That sounds like a reasonable argument but for two things: (1) most pastors’ attempts at “explaining” the Lord’s Supper degenerates into making it about something else (sometimes through unfortunate uses of metaphor or similes—“It’s like….”—and I think I’ve heard just about every one, from “It’s like being part of a family†to “It’s like a football team.†Hint: No, it’s not “like†those at all!) and fail to present exactly what it IS; and, more significantly, (2) the meaning inherent in rites, practices, and symbols, like the Lord’s Supper, are not acquired through “explanation.” They are acquired, even “learned,” through witness and participation in the rite itself directly. Symbols speak for themselves, they don’t need to be explained—to attempt to do so robs them of their power (and, as Jung said, reduces them to mere “signs.”). Rites carry their own meaning in the practice and participation, not in explication. I suspect that the urge to “explain” rites and rituals like the Lord’s Supper may be evidence of a lack of faith in what they are as much as a misunderstanding of their nature as transformative and mediative components of corporate faith.

So, pastors, please, next time you offer the Lord’s Supper, don’t feel you need to be “creative” or “imaginative” in presenting it. It’s a simple rite, and as such, elegant in its essential form. Don’t attempt to “explain” it to me—I know what it’s about. Don’t cover your nervousness, performance anxiety, lack of tolerance for sacred silence, or insecurity by using the noise of verbiage. If you need to say something, then just repeat the words of institution for they speak elegantly and directly about what this is about. The familiarity of the words, heard again, committed to memory through hearing and repetition over the years is a comfort and affirmation of something meaningful—your words are a distraction. This important thing we do together, that you are called to lead, is not about you or your performance. It does not belong to you; it is not yours to re-invent, dress up, or re-interpret—it belongs to the Church body. Stop messing with it. (I did say this was a rant, right?).

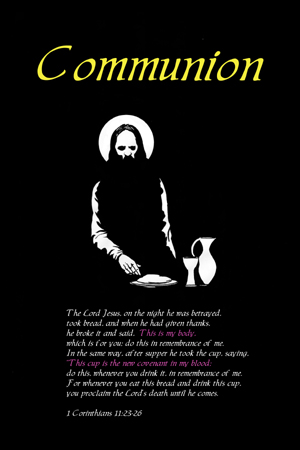

If you need a reminder, here’s a “Communion†poster with the words of institution from 1 Corinthians 11.

“I do not feel obligated to believe that the same God who has endowed us with sense, reason, and intellect has intended us to forgo their use.” Galileo Galilei

Pingback: I want to be unfriendly and irrelevant | G.R.A.C.E. Writes

Pingback: Things that would cause me to walk out on worship | G.R.A.C.E. Writes

Pingback: We could do with some rules around here | G.R.A.C.E. Writes