During a hallway conversation with a former minister who recently took a job in educational administration the topic of the newbie learning curve came up. He unburdened about how, after a year on the job, he was still on a learning curve. I shared with him that I tell seminarians that it takes about three years to become competent at a new job. He laughed and recalled how he had to learn that lesson the hard way in his early pastorates. Now, he says, he tells starting clergy to not do anything for about two years, and then, to “only take baby steps†when trying to bring about change.

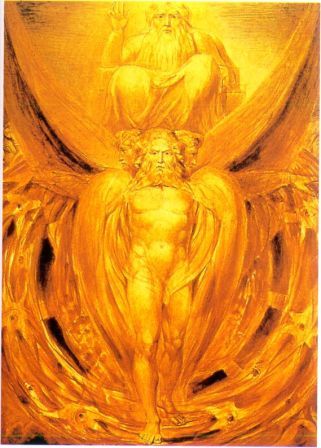

“Ezekiel’s Vision of God” by William Blake

I’m still convinced that clergy can’t really do “that vision thing†till they are in their fifth year at their congregations. It just takes that long to get to know the complex matrix of culture, corporate identity, and network of relationships that constitutes a congregation well enough to formulate a vision. I usually get two responses to that statement: (1) a shake of the head that it’s too long, and, (2) a nod that it’s about right. Given that vision is a key function of leadership I can understand why leaders are eager to offer it. But offering it during one’s first year at a congregation always strikes me as both misinformed and willful.

Vision is important, but it doesn’t arise out of thin air. And it isn’t something that is disconnected from other informing factors, like context, personal and corporate values, relationships, mission or what Stephen J. Trachtenberg, former president of George Washington University called a “point of view.†He has an interesting perspective on “that vision thing†that appeared in The Chronicle of Higher Education (Nov. 2, 1007, p. B5). Here’s what Trachtenberg wrote in an article titled “Lessons From The Topâ€:

Another lesson is about leadership, a simple word that has acquired a peacock tail of complexity trailing behind it. I want to offer just one bright feather. Leadership, we read in endless management books, requires “vision,†so a leader needs to be “a visionary.†We shouldn’t believe that. Ezekiel was a visionary, and Chapters 1 and 37 of Ezekiel in the Old Testament are moving and some of the finest scriptural eloquence we have. But I doubt that I am alone in being confused about the wheels in Chapter 1 and the dry bones in Chapter 37. Sometimes it is better to be concrete than eloquent. It is better to have a point of view or a series of goals than a vision that is subject to many interpretations or baffled silence.

That perspective rings true for me, especially if by “point of view†he means something akin to a philosophy or set of guiding principles that facilitate discernment about what is important and what is not, about what is expedient and what is right, or about what is urgent to address and what can wait. And while a vision can inspire, inspiration without perspiration tends to get you nowhere. People may stand and applaud a vision, but concrete goals will get them to roll up their sleeves and get to purposeful work.

Pingback: Margaret Marcuson