I continue to be fascinated with how people are enamored with the idea of mentoring. It seems to have a romantic hold on people’s imagination. I recently received an e-mail from a friend who is a college program director. She was asking some questions about a program for college students being created at her college. The program design looked pretty good, though it included a “mentoring†component. I sighed and cautioned my friend about the tendency to misapply “mentoring.†Much of what people do under the rubric of “mentoring†isn’t appropriate to their goals, aren’t applicable to their audience, ignores the significance of context, and isn’t designed to be mentoring at all.

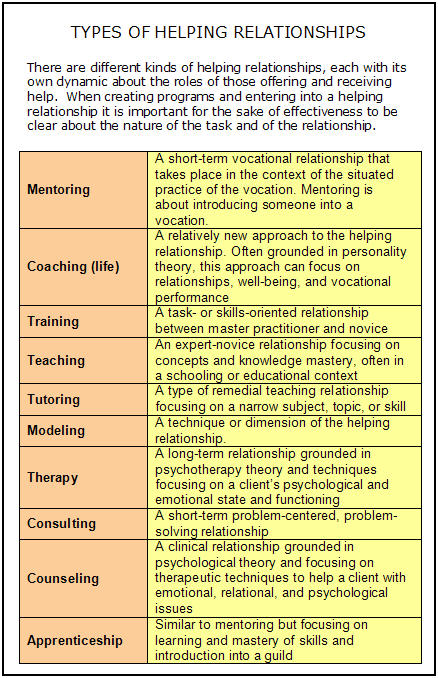

I’m always amused at how passionately people defend what they are calling “mentoring†when it is, in fact and practice, something else (training, apprenticeships, coaching, internships, modeling, discipleship, “spiritual friendships,†or other “learning relationshipsâ€). Ultimately I just give up and say, “You can call it mentoring if you want—I really don’t care what you call it. Just be careful that you aren’t convincing people that they are mentoring, or being mentored, when they are not. That’s unfair.â€

Here are the dynamics behind why I think this is important:

- In order for any educational approach or practice to be effective it must be applied rigorously according to its principles and it must be congruent with the desired outcomes.

- To confuse one approach for another renders what we do ineffective.

- To confuse the means to an end runs the risk of rendering the wrong ends.

Additionally, in any helping relationship three interrelated dynamics are at play: (1) Reciprical bounded relationships, (2) the intended (and unintended and null) functional goals of the relationship, and (3) the situated context that defines, facilitates, or inhibits the first two. For those reasons I tend to define mentoring narrowly in order to respect the nature of the practice. To do otherwise is to risk being ineffective or confusing one approach for another (in other words, doing one thing while actually doing another). Strictly speaking, I define mentoring as: Mentoring is a vocational relationship that takes place in the context of the situated practice of the vocation. Mentoring is about introducing someone into a vocation.

Mentoring has these characteristics:

- It is a bounded relationship (mentor-mentee) that has a narrow window for when it begins and when it ends.

- It is a volitional relationship. Making mentoring an “assignment†or a requirement in a program removes this important dynamic.

- It involves an introduction into the guild of the profession, the proctored mastery of vocational skills, but also the withholding of knowledge.

- It has a developmental component, namely, it is for those at the entry point of vocation—therefore, not for those in preparation for a vocation. This is why we see Andragogical principals of learning in formal mentoring relationships. Those being mentored need to be young adults (emphasis on adults), not adolescents or post-adolescents or those in a state of protracted adolescence.

Therefore, it is not appropriate to define something like parenting as a “vocation†and then create a program that provides elder “mentors†to young parents. And, certainly, then, you can’t “mentor†children.

These concepts about the nature of mentoring challenges the misguided notion that seminaries can provide “mentoring†to future clergy as part of their educational experience. More specifically, it is a mistake to believe that seminary professors whose profession and vocation is the academic classroom and whose focus of interest is a field of study (preaching, Biblical studies, and even practical theology) can be mentors to clergy who will serve in congregations. For example, when I was a congregational educator I could be a mentor to someone wanting to be a congregational educator. But I’m eight years removed from that situated vocational context. So, even though I teach in the field of congregational Christian education I can’t be a mentor to someone who wants to be a congregational educator, but I can be a good mentor to someone who wants to be a seminary professor in the field of education, or perhaps wants to be an educator.

That does not mean that my teaching relationship cannot be helpful to future clergy or educational educators. I can be teacher, coach, model, trainer, etc. But I don’t fool myself into thinking I can be a “mentor†to someone entering vocational ministry. For one thing, the situated learning context in which I work dictates a bounded relationship. As long as the student is in seminary I will always be “teacher†and he or she always “student.†Unlike the mentoring relationship which assumes that at one point the person being mentored will achieve a level of competence and mastery and will outgrow the mentor-mentee relationship, as long as the student remains in seminary he or she will always be a novice. (The power of this dynamic can be seen in the inability of alumni who, years later, still cannot bring themselves to call me anything other than “Dr. Galindo.â€).

Nor will I be unfair by accepting an invitation from a student who wants me to be a “mentor†if they are entering congregational ministry. They’ll find their mentor in the context of their vocational setting. There is that old saying, when the student is ready, the teacher will appear. Seminarians are not ready to learn the things I think they really need to know and understand about ministry while they are in seminary. They will learn those important things when they need to learn them in the situated context of their vocational practice of ministry.

“You can’t plant insight into the unmotivated.” M. Bowen

Copyright (c) 2007, Israel Galindo. All rights reserved.

1 Response to On mentoring